The story of the Galveston Ragworm

I am now on my sixth year of studying the population, reproduction, and morphology of Galveston’s top Ragworm, Alitta succinea. Come the spring, I’ll have a pretty comprehensive story describing the life cycle of these worms. Hopefully, this detailed dissertation will be enough to convince my colleagues I’m worthy of the tile “Worm Dr.” - we’ll see!

Alitta succinta.

These worms are from the family Nerididae, and usually don’t get any larger than 4-6cm, or 2-3 inches. The live in the sediment, in algal mats, oyster reefs, and pretty much anywhere else on the coast. They are omnivores and will consume algae, detritus, some crustaceans, and even other worms. Most of their life is spent crawling around their environment, sometimes on the surface of the sediment and sometimes through mucus tubes they create.

Once these worms reach the exciting age of reproduction, they undergo a metamorphosis similar to a caterpillar. They will stop eating, and their body will change shape. In preparation for reproducing, a few key structures change. Their eyes (of which they have two pairs) will grow larger. The muscles they use to crawl will change into muscles adapted to swim. Additionally, their bristles change from thin and pointy to flat and paddle-like -again to help with swimming. Lastly, their gut with dissolve and their body will fill with gametes (eggs or sperm).

Image of the floating docs on Galveston’s campus. Alitta succinea lives in the algal mat fouling communities that grow on the black floats.

Now the fun begins. When it is time to reproduce, these worms will leave the sediment in a choreographed mass exodus and swarm at the surface. It’s an incredible show when hundreds of worms will swim together and shead their gametes. After they release their gametes, these worms die from exhaustion. This is similar to what happens when Salmon swim up stream to reproduce.

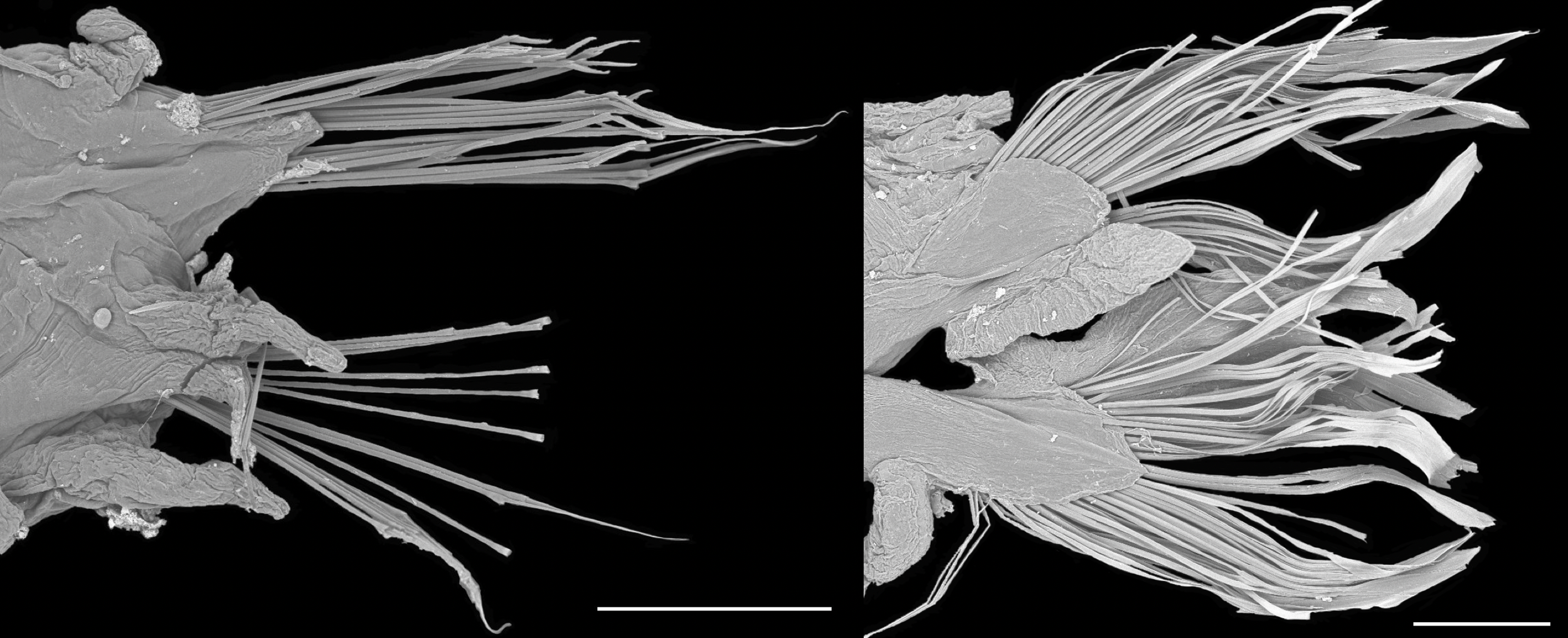

Scanning electron micrographs of parapodia (think limbs) of Alitta succinea. The left image is taken from a non-reproductive worm that has bristles for crawling. The right side is after metamorphosis when the worm has bristles adapted for swimming. SB is 200 microns.

For my dissertation, I conducted three projects to better understand how Alitta succinea reproduces. First, I monitored their population dynamics over two years. I’ve collected data on population numbers, reproductive stages, and tracked growth with measurements of over 2,000 worms! I then focused on their morphology and am describing just how different their musculature is before and after metamorphosis. Lastly, I studied the molecular drivers behind the different sexes and how they differ in reproduction.

I’m wrapping up all my data and will share it as it comes out!